Dichotomy and Pairs in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

Dichotomy and Pairs in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man Meaghan S6

English 12 H

2.7.08

In

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce juxtaposes elements in Stephen’s life as contrasting pairs to emphasize the division he feels within himself. These pairs include the clashes between religion and politics, love and lust, fantasy and reality, and the ultimate conflict between male and female. According to feminist thought, children learn this contrast at a very young age, when they are first learning language. When the child is fully able to recognize this distinction, it signifies that a clear differentiation has been made between the mother and the father. As he ponders these thoughts, Stephen slips into a state of confusion. Through the juxtaposition of these contrasting feelings, Joyce suggests that the intoxicating power of memory and its relationship with the current state can drastically affect the mentality of an impressionable teenager and his growth into adulthood.

In the case of Stephen,ation has been made between the mother and the father. , when they are first learning language, and thisIn the passage in Chapter 1 when Stephen recalls the boys at school stealing wine from the sacristy, Joyce contrasts Stephen’s different takes on sin and religion through the religious or “ecclesiastical” (Henke 331) mother and his departure from it. Stephen first explains that “it had been found out who had done it by the smell” (Joyce 54). The sense of smell is tied very heavily to memory, so the fact that the boys are caught by sense of smell implies that the memory of what they did is potent enough to stick with them because it essentially brought about their demise.

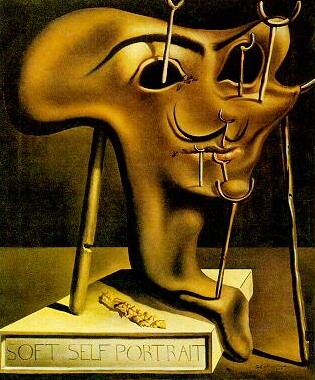

When Stephen next addresses the issue of sin, he declares that it “must have been a terrible sin” (Joyce 54) to “steal the flashing gold thing into which God was put on the altar” (Joyce 54). So, it is Stephen’s first instinct to see the sin in this situation, which implies he has been brought up with morals that reflect his religion. The image of flashing gold represents the power the chalice holds, as gold is normally connoted with power, authority, and masculinity. In the idea of dichotomies, religion is typically related to the feminine side, but the reverence Stephen has for the gold chalice suggests his fear of God as a paternal threat. According to psychoanalytic criticism, “a series of father figures…knock Stephen down” (Brivic 282), and God is the one that Stephen fears the most.

However, Stephen challenges this authority with curiosity and confusion. Stephen logically and innocently states that “God was not in it of course when they stole it” (Joyce 54). Though it shows that he is beginning to think more rationally, it also shows that he is starting to question the beliefs that he grew up with. Stephen also calls the boys’ actions a “terrible and strange sin” (Joyce 54) that “thrilled him” (Joyce 54). This is a sign of Stephen’s insecurities and confusion because he realizes his inner conflict between what he has been taught and what he is developing in his own mind.

Stephen further goes on to explain the memory of the smell of wine that made him “feel a little sickish” (Joyce 54). Similarly to the boys who stole the wine and were caught by the smell on their breaths, Stephen recalls his “first holy communion” (Joyce 54) when the rector “had a winy smell off [his] breath after the wine of the mass” (Joyce 54). This imagery of smell is tied strongly to one of his earliest religious memories, and in the Catholic religion, the first communion is supposed to be the “happiest day of your life” (Joyce 54). This is a childhood memory of Stephen’s, and he remembers calling it that because his family or other religious influences at school referred to it as such. Stephen also acknowledges that Napoleon said “the happiest day of my life was the day on which I made my first communion” (Joyce 55). His recognition of Napoleon’s beliefs indicates that he also sees Napoleon as a strong paternal figure. Thus, the contrast between the feminine connotation of religion and the male influence of a renowned leader like Napoleon also develops Stephen’s confusion regarding religion.

To end the passage in between the religious references, Stephen describes the connotations he has of the word wine. He says it is “beautiful” (Joyce 54) and makes him think of “dark purple because the grapes were dark purple that grew in Greece outside houses like white temples” (Joyce 54). Calling the word beautiful suggests that Stephen is starting to find an appreciation for words because beautiful has a strong tie with things that are heavenly or unable to be described in any other way. French feminists tie language to the “period of fusion between mother and child” (Henke 300) and the eventual “separation” (Henke 300) of mother and son. So, as Stephen is learning to be independent and have his own thoughts, he is forsaking what he has been brought up with, namely what his mother taught him. His appreciation for language and words is indicative of the art he wishes to pursue, and in turn, to follow his dream, he must let go if his past and start anew.

Also, drawing on the reference to Greece and using the simile to compare the houses to white temples also suggests a heavenly feeling because of how spiritual temples are. The contrast of white houses and dark purple grapes through color imagery is also indicative of Stephen’s confusion because he is battling between conflicting feelings. The white of the houses, as in religion, represents purity and the feminine, while the dark purple represents the darkness or sin that often tries to overtake the purity, as with the grapes growing over the houses. The imagery here could also relate to Stephen’s mind. A “temple” (Joyce 54) is also a part of the head typically associated with the brain, so the “grapes” (Joyce 54) represent the growing thoughts within Stephen’s mind that are overtaking the ideas he originally had.

Though Stephen is fairly young when the wine incident takes place, he cannot help but feel the struggle between boyhood and adolescence. He battles with the aforementioned religious topic, as young adults often become more quizzical and question what they have been taught. Later on, he also toils with the location in which he lives: the “political” (Henke 331) mother.

In Chapter 2, Stephen’s family is facing financial problems, so they are forced withdraw him from his school and move to Dublin. In Dublin, Stephen looks to find adventure and answers to his complex questions. He sees himself through the story The Count of Monte Cristo and imaginarily falls in love with the character Mercedes. He looks up to the character of Edmond Dantes as “his model” (Henke 322) because he sees Dantes as “an isolated hero who eventually conquers the woman he loves through a complex process of amorous sublimation” (Henke 322). Therefore, he battles with differentiating fantasy from reality because he can only picture himself the fantastic setting of Dantes’ world.

With the new territory of a new city comes a new liberty. Stephen becomes “freer” (Joyce 70) and roams the city, looking vainly for Mercedes. He makes a “skeleton map of the city in his mind” (Joyce 70) in order to trace the streets, describing his passage as “unchallenged” (Joyce 70). The word unchallenged suggests that Stephen is completely unrivaled, with no one checking his actions and the ‘skeleton’ reference indicates that he sees the area as barren, cold, and empty. This is very different to what he experiences at school, where he is constantly monitored. Now that his family has transitioned into a new home, he is able to do as he pleases, and these new privileges bring about conflict because he does not now how to handle it.

As Stephen wanders through the streets of Dublin, the “vastness and strangeness” (Joyce 70) of life hit him again. This pair of nouns reflects Stephen’s ambiguity and confusion regarding his surroundings because he looks at it in terms of its massive size, but also how foreign it appears to him; he seems very uncomfortable. He walks from “garden to garden in search of Mercedes,” (Joyce 70) passing by the “bearded policeman” (Joyce 70) and the “bales of merchandise stacked along the walls” (Joyce 70). This vivid imagery of the town shows how overwhelmed Stephen is in a new city because he was very sheltered in the small community at his school. However, as he reminisces back to his old town, he misses “the bright sky and the sun-warmed trellises of the wineshops” (Joyce 70). In this way, his very intricate memories manipulate his thoughts. The warmth given off by the shop in contrast to the cold feeling of wandering the streets alone suggests that even though he is in a new place that will bring him adventure with fantasies like Mercedes, he still dreams of the comfort of his old home. Stephen then remembers the feeling of “vague dissatisfaction” (Joyce 70) but “continued to wonder up and down day after day” (Joyce 70). Though he knows that she is not real, he still continues to sulk around looking for her, a wild figment of his imagination. The repetitive back and forth motion, which can be interpreted as a pair as well, ultimately relates to both his futile search for Mercedes and his inner conflicts over what reality really is.

As the novel progresses, Stephen is shrouded in doubt and cannot seem to grasp a single, solid feeling. He continues to struggle between the “binary pairs” (Henke 300) he encounters throughout his final years at school, especially with regards to his feelings about women. Even as the novel comes to a close in Chapter 5, Stephen continues to brood over the duality he feels in his daily life, especially with his confusion between love and lust.

In Chapter 5, Stephen develops feelings for a girl named Emma, but he is unsure of the intentions of these feelings. He experiences many lustful images of women, but believes to a degree that his feelings for Emma are stronger than that. She walks past both Stephen and Cranly, but only acknowledges Cranly. Stephen notices a “slight flush on Cranly’s cheek” (Joyce 206), which infuriates him. As a result, he “could not see” (Joyce 206). Joyce suggests that Stephen is blinded by his anger, and according to psychoanalytic criticism, “the loss of eyes is an image of castration” (Brivic 281). This moment, therefore, is indicative of Stephen’s feeling of losing his masculinity. He is unable to elicit a reaction from Emma, while Cranly is able to garner her attention. Stephen even goes as far as to call Cranly’s actions “rudeness” (Joyce 206) because he had once trusted Cranly with his “wayward confessions” (Joyce 206). Stephen is constantly let down and chastised by the male influences in his life, so Cranly’s ‘betrayal’ reminds him of when he “dismounted from a borrowed creaking bicycle to pray to God in a wood” (Joyce 206). However, “two constabularymen had come into sight round a bend” (Joyce 206) and “broken off his prayer” (Joyce 206). Stephen already sees God as a paternal threat, but men who approach him intimidate him so much that it halts him in mid-prayer. By using this comparison, Joyce juxtaposes Stephen’s fear of paternal threats that are both divine and mortal.

Stephen questions for a moment if Cranly had “heard him” (Joyce 206) but then automatically responds that “he could wait” (Joyce 206). Though the pronoun “he” is ambiguous, it is most likely referring to Cranly because Stephen incredulously questions Cranly’s intentions but automatically shifts his attention back to Emma. She “passed through the dusk” (Joyce 206) as the “air was silent…and therefore the tongues about him had ceased in their babble” (Joyce 206). It seems as though those tongues are the voices in Stephen’s mind that present him with constant struggles and conflict. Emma “provides a substitute for the mother” (Henke 334) because as previously mentioned, Stephen is enduring a struggle to remove himself from his three different mothers and has nowhere to turn in his time of need. In place of the three that he is separating himself from, Stephen is looking for a culmination of protection, strength, attraction, love, and lust, and he believes he has found it in Emma.

The conflicting voices in Stephen’s head, however, are pacified when he acknowledges the darkness. Stephen then misquotes a poem by claiming that “darkness falls from the air” (Joyce 206). The original line of poetry had “brightness” (Joyce 206) instead of darkness. Darkness and brightness, typically two opposites, do not often work interchangeably. However, Stephen replaces the word because he feels more comfortable in darkness. The brightness blinds him, as in the aforementioned paragraph, so the darkness settling in signifies that he is becoming more comfortable with his thoughts. He continues his path toward the darkness as “he walked away slowly towards the deeper shadows” (Joyce 206). Stephen can take solace there because he knows that there is no threat and he is in control.

Once Stephen reaches the darkness, however, his eyes “open from the darkness of desire” (Joyce 206). Any time the eyes open, it signifies a rebirth or reawakening, so at this point Stephen begins to see differences between himself and Cranly and how differently Emma sees both of them. Although Joyce explains that the darkness represents desire, Stephen still feels the most comfortable there because desire is all he knows. He cannot create a meaningful and lasting relationship based on emotions or feelings, so he chooses to live his desires through fantasy. Stephen, though “horrified by the realization that he has besmirched the icon of his beloved Emma by making her the object of his…fantasies,” (Henke 326) continues with his thoughts of her; he cannot resist the temptation. Stephen then “tasted the language of memory ambered wines” (Joyce 206). This implies that he is looking into his past, which has aged over time to develop into the feelings he has now.

This is further exemplified by Joyce’s juxtaposition of two different types of women. He sees “kind gentlewomen in Convent Garden wooing from their balconies” (Joyce 207) who are nuns or other types of religions women, and “poxfouled wenches of the taverns” (Joyce 207) who are women that are looked down on by society like prostitutes similar to the one he experiences. The women of the Convent are described with more delicate diction, like ‘kind,’ but the other women are referred to as ‘wenches,’ which is a word with a very strong connotation of dirtiness and impurity. According to Freudian thought, boys see “two aspects of women” (Brivic 287), one being the “virgin” (Brivic 287) and one being the “temptress” (Brivic 287). Stephen examines both types, as he can “dictate his actions” (Brivic 287) to the virginal type but can “find expression” (Brivic 287) in his fantasies of the tempting type. Unable to decide which he feels about Emma, Stephen realizes how both types of women “yield to their ravishers” (Joyce 207). In the religious women’s case, they answer to God, while the others answer to men who seek comfort in their bodies and sin. Stephen realizes that he “sees both in Emma” (Joyce 287) because he both fantasizes about her and can see himself in a relationship with her, but he continues to remain torn. Stephen’s ability at the end of the novel to make this distinction shows how he has developed into a young man, but it is this ability that tears Stephen away from women and pushes him toward his art.

Stephen’s conflicting feelings stem from the contrast between opposing forces. The Greek god Dionysis is a perfect example of this dichotomy that Stephen faces. Dionysus is the god of wine, but is also the god of intoxication. This contrast clearly represents Stephen’s situation because he is caught in between what he has been taught and what is logical, between the real world and his imagination, and between feelings of love and lust. The wine that Dionysus represents is a pure substance, as it is used in sacraments in the Catholic Church as the blood of Jesus. However, too much wine can cause a person to become drunk, and being under the influence elicits a person to think or say things they typically would not think or say otherwise, just like Stephen does when he contemplates the theft of the wine, Mercedes, and Emma. Overall, these pairs rule Stephen’s life and his decision making process because he is unable to see one side of something without another side to compare it to.